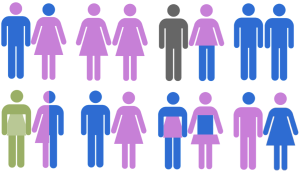

Getting away from the binary

We humans like to simplify the world into understandable chunks or stories. When we’re thinking and talking about sexual or partner violence, it’s so easy for us to think about men’s violence against women. It’s understandable — this is probably what the majority of these kinds of violence looks like. Defining violence this narrowly also makes it easier to measure what’s going on and what kind of changes our programming makes.

We humans like to simplify the world into understandable chunks or stories. When we’re thinking and talking about sexual or partner violence, it’s so easy for us to think about men’s violence against women. It’s understandable — this is probably what the majority of these kinds of violence looks like. Defining violence this narrowly also makes it easier to measure what’s going on and what kind of changes our programming makes.

But men’s violence against women is just part of the picture. And it’s a part of the picture that I think has come to represent the whole in ways that might be harmful to people whose experiences don’t fit in that picture. What about people who don’t identify with either side of that binary? How are we addressing how patriarchy and oppressive norms hurt them? And how are we ensuring that our programs and our messaging aren’t heterosexist? Of course we want to avoid homophobia, but how can we also make sure our programming isn’t based on the assumption that everyone in the room identifies as a man or a woman and/or is attracted to only members of the “opposite” sex and gender? And are we making it worse for those we leave out by failing to address their experiences?

In response to a blogger writing this simple sentence: “Most men aren’t rapists; some women are rapists; some people who aren’t men or women have experiences with sexual violence,” a reader commented:

Thank you. Thank you so much. I am genderqueer and was raped 4 years ago. And I have never had my experience validated before in anything I have heard. I have been mis-gendered, mis-believed, and mis-treated in every step of my healing process by law enforcement, therapists, other feminists and my own friends.

I know a lot of us believe that most men aren’t rapists, that some women are rapists, and that some people who aren’t men or women have experiences with sexual violence. So why do we still leave these ideas out of so much of our work? As far as I know, the prevention research that measures changes in sexual violence perpetration behaviors only measures them among men. Engaging men is a big part of our current work, and I often write about preventing violence against women. Noticing a theme here?

From that same article:

There’s a ton of problems with this set up, not the least of which is painting women broadly as victims and men as perpetrators. Another way gendered violence functions is by erasing the many people whose experiences of sexual violence don’t fit this model – survivors who are men (cis or trans), trans women, genderqueer, two spirit, or in some other way gender non-conforming, intersex folks, and survivors of crimes perpetrated by atypical attackers, like survivors of queer relationship violence. Sadly, feminists end up perpetuating this exclusion when we talk about victims only as women and perpetrators only as men. Rape is absolutely a gendered crime, but the act of rape itself doesn’t necessarily follow those rules.

We need to continually recognize sexual violence as both “embedded in a gendered culture of violence” and an act that people who have any (or no) gender identity can commit and experience. And we need to make sure our work reflects these understandings.